Swimming to Survive: Identity Formation and Gifted Kids

I have had a strange fascination with Michael Phelps for years. I’ll chalk it up to his being a Baltimore hometown hero, so his accomplishments have gotten a bit extra coverage in my neck of the woods. As a gifted athlete who surpasses the imagination of possible goals, Phelps has literally stood on a pedestal, with the world in awe of his achievements. And yet, by the age of 19, already a 4-time decorated Olympian, Phelps had two DUI arrests under his belt and his struggles with alcohol and marijuana were making headlines. Phelps gives us an excellent case study in identity formation and gifted lives.

People started asking: How could such a talented athlete throw so much away?

During the 2016 Summer Olympics, totally by chance, I caught an extended interview with Michael Phelps. While talking to Bob Costas, Phelps discussed how growing up – without swimming – he had no sense of self (see 7:55 in the video) and how people around him had little idea about who he really was as an individual (8:25). He eventually hit rock bottom and thoughts of suicide subsumed him (10:00).

Listening to the interview, I had a variety of ah-ha moments at very personal, as well as professional levels.

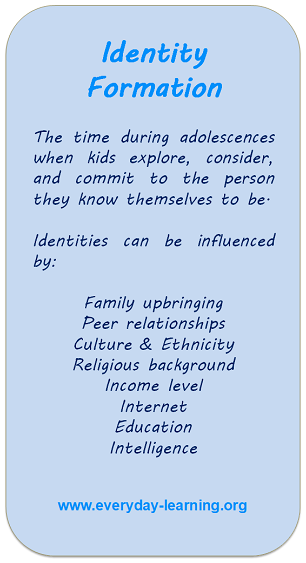

Identity Formation and Gifted Kids

Now, I recognize in the gifted world a segment of folks hold a certain level of resentment for the financial funding that supports sports programs for talented athletes. I’m not going to get into the politics of funding formulas, but I do want to examine the similarities that exist in identity formation and gifted children.

Much like prodigious athletes who are showered with accolades and attention, profoundly gifted students who elicit the WOW-factor in others can grow up and easily lose their sense of self, much in the same way that Phelps described.

Growing up can be hard when you’re 10-years old and you hear things like, “OMG, you’re smarter than me and I’m 50!” OR “I bet you’ll be the person who cures cancer!” The well-intentioned “genius” or “Einstein” moniker can easily replace Jane or Johnny’s burgeoning self of sense.

Think about it: How easily can a person get to know the core of their own being when the world around them only wants to know them for one thing – their IQ?

On the one hand, the attention is addictive. Who doesn’t like compliments and being made to feel special for being able to do things that many of your peers can’t do? On the other hand, feelings of guilt can also kick in. For some of these kiddos the kudos they get are for abilities that come as naturally to them as walking does for most other people. In either case, this kind of attention directly impacts identity formation and gifted kids.

In no way am I saying that radical acceleration or early college are bad educational options for highly and profoundly gifted kids, tweens, and teens.

For some children, having the opportunity to intellectually engage with academic content and peers who can discuss higher order concepts can – in itself – literally save a life. BUT – and this is the important point – I think the push over the last 10+ years on talent development and for younger and younger college entrance needs to be rethought.

Michael Phelps has continued to talk about his struggles with anxiety and depression. In a 2017 Today Show interview, he said, “I was very goal-oriented and very passionate about what I was doing and wanted to be the best” and yet he admits he had “no self love” – even after mind-boggling Olympic successes. In fact, he really just wanted to die.

Coaches, teachers, mentors – and even some parents – do our brightest and most talented youth a disservice when we groom them for great achievements, yet the child comes away from unimaginable success despising the “personified perfection” the world sees in them.

In 2018, Michael Phelps returned to the Today Show to continue talking about his struggle with depression. He shared, “I was probably hiding a bunch or compartmentalizing a bunch of the stuff I was going through just because I was always taught that we weren’t allowed or weren’t supposed to show a weakness … because of being an athlete you’re supposed to be strong and be able to push through anything.”

The Gifts of Boredom and Failure

So, what can you do to support identity formation and gifted children (academic, athletic, or musical ones) so that they may succeed as a whole person? Let them be bored and – yes I’m saying this next part – let them fail without denigration.

Through boredom a person can discover and explore interests that serve no other purpose than relaxation and entertainment. Boredom gives a person the opportunity to wander aimlessly within their own mind or the world around them and discover new things they hadn’t noticed before.

Through failure a person can learn to embrace the imperfections that inherently weave our lives together. Those imperfections may be the slightly crooked tooth that does not require braces. Or, it may be the inability to sing on key (yeah, that’s me). Or, it may be the fact that we just sometimes have off days and despite our best preparations we’re not going to always be on our A-game. Those imperfections do not make us less worthy of attention or even love, they simply make us human.

I have great respect for Michael Phelps – not because he is the most decorated Olympian in the history of humankind – but because he has the humility and courage to share his story, one which I hope resonates within the gifted community.

Aspiring for great achievement is not bad. Singularly aiming for accolades at the expense of loosing sight of one’s self, however, may extract too high of a price from our precious prodigies.