Slow Processing Speed: When Is It a Problem

It happened again last week. A mom called with a freshly printed test report that showed a 26-point discrepancy between her daughter’s Verbal Comprehension Index and her Processing Speed. Mom was concerned – no, strike that – furious that the evaluator had not diagnosed dyslexia. The daughter wasn’t failing any classes, but mom felt like her grades should be better. Mom wanted a 2nd opinion and help with putting together an Individualized Learning Plan.

What is Processing Speed?

Processing Speed measures the cognitive ability responsible for a person’s speed and accuracy in making decisions about some type of information. For example, right now you see a bunch of letters on a digital screen. Your brain is processing the letters into words and sentences to make meaning of what I’m trying to communicate in this blog post.

When a student presents with a Processing Speed score 20+ points lower than other index scores, we need to stop and consider what’s going on. BUT, and I need you to read the next part of this sentence more than once, please: Low Processing Speed does NOT automatically mean a child has a learning disability. To understand why this is true, we have to look at how Processing Speed is usually measured.

IQ Tests and Processing Speed

The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 5th edition (WISC-V), one of the most widely used IQ tests, uses 2 subtests to come up with a Processing Speed Index score. The Coding subtest requires a person to look at a box of numbers and corresponding symbols and then correctly copy as many symbols as they can write on a worksheet. In contrast, the Symbol Search subtest has a person look at a sheet full of symbols and circle all the ones that match a group of target symbols. Both of these subtests are timed and require a certain level of fine motor skills.

The subtests can provide us with important information about a person’s ability to concentrate on a task and visually scan and discriminate details on a page. Most importantly, the subtests give us a sense of the person’s rate of visual-motor coordination. The limitations, however, are that the subtests only probe a person’s short-term visual processing speed and their ability to produce some type of written work. Because the subtests are purposefully abstract and do not require any prior learning in order to do well, they also fail to tell us anything about a person’s Processing Speed relating to long-term memory storage of information.

Achievement Tests and Processing Speed

Individualized achievement tests, like the Woodcock-Johnson Test of Achievement (WJ) and the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test (WIAT), measure Processing Speed through fluency tests. Fluency tests check to see how quickly and accurately a person can complete a series of rote tasks, like correctly writing answers to as many basic addition, subtraction, and multiplication facts as they can in a certain number of minutes.

In each of the reading, writing, and math fluency subtests, processing speed is measured in terms of visual input and fine motor skill output. The limitations with measuring Processing Speed this way is that it does not capture the full range of receptive and expressive language skills that people use every day.

Many schools and teaching methods rely heavily on visual input and written output for measuring academic achievement. Low Processing Speed, as measured by these standardized tests, may then explain why a student is getting lower-than-expected grades.

But here’s the funny thing about Processing Speed: In the real world, we process more than just the visual presentation of letters and numbers. And – this is super important to acknowledge – people are expected to respond in more ways than just writing. That is why a low Processing Speed score on an IQ test does not necessarily mean your child will struggle and underachieve in school and in life.

So How Do You Know If It’s a Problem?

Even without failing grades, parents, like the one who called recently, can become concerned when they discover their student has low Processing Speed. While I understand the fears, it’s useful to remember 3 fundamental truths about academic evaluations.

Rule #1: NO single test score can or should be used to diagnose a learning disability, such as dyslexia, dyscalculia, or dysgraphia.

Rule #2: Low Processing Speed can be caused by any number of issues.

Rule #3: Test results should always be considered in the wider context of the whole child.

When a student with low Processing Speed is not significantly below grade level, but the parent believes the child is working below their ability, a first step involves examining non-academic factors that could have impacted the score results, such as:

- Poor pencil grip

- Poor muscle tone in the hand

- Recently injured the arm, wrist, or hand

- Minimal handwriting practice

- Needing eyeglasses

- Bored with the task

- Overthinking questions

- Coming down with an illness, such as the flu

- Nervousness

- Perfectionism

- Overly tired

- Distracted by hunger or need to use the bathroom

- ADHD

- Concussion

- Emotional distractors, such as the death of a family member or beloved pet or parental fighting or divorce

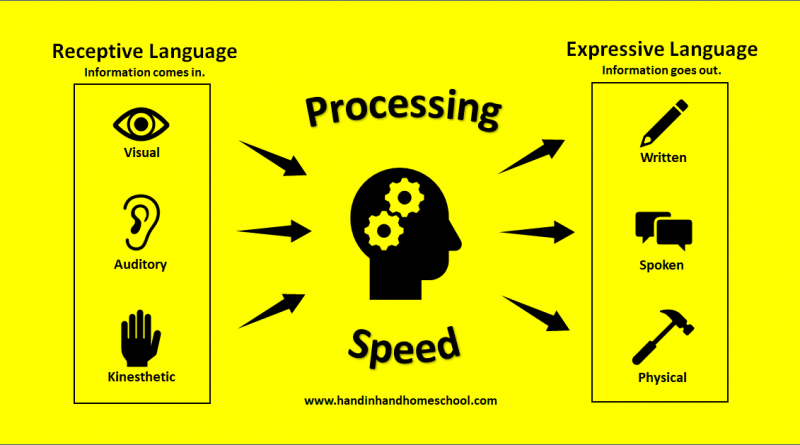

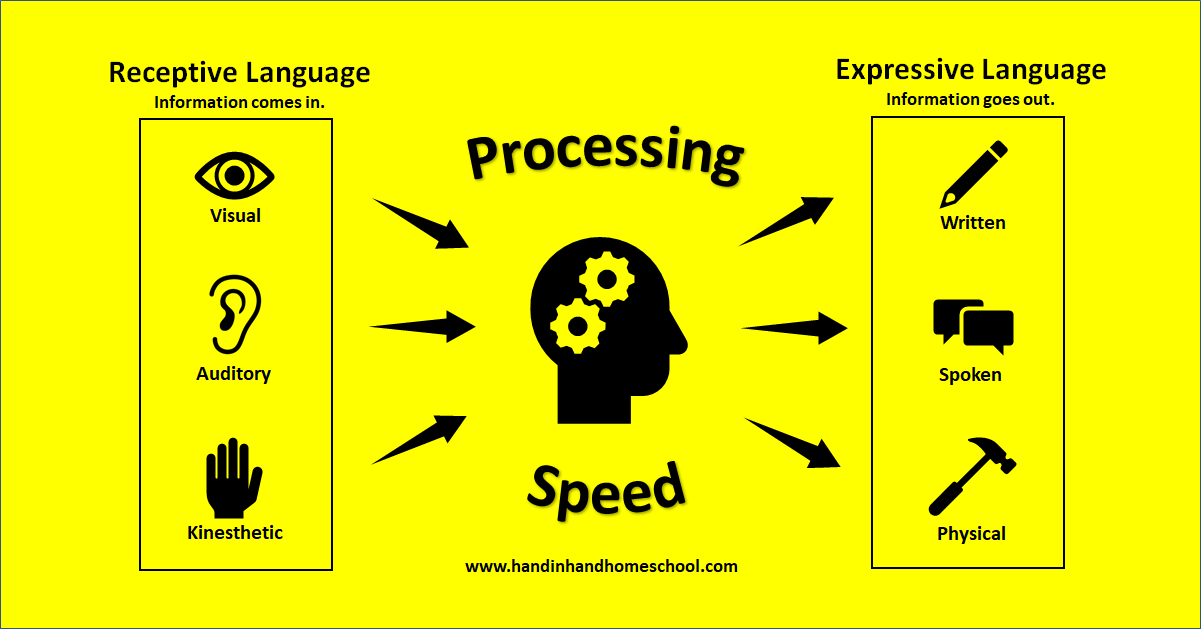

Should non-academic factors be ruled out, we can then take a look at specific Receptive and Expressive Language skills. Receptive Language is how we take in information – through reading, listening, or seeing a demonstration. Expressive Language is how we communicate facts and ideas – through writing, speaking, or doing something.

Some questions to ask when trying to sort out low Processing Speed include: Does/can the student:

- Experience slow processing in reading, math, and writing – or in only one of these areas?

- Excel with a specific Receptive Language modality, such as listening to an audiobook versus reading by themselves?

- Refuse to write but willingly discuss material they’ve learned?

- Prefer to create learning products that involve minimal speaking?

- Make many errors in their work?

- Work extremely slowly, but error-free?

Exploring these questions with input from different teachers who work with the child helps to sort out IF, HOW, and WHEN low Processing Speed impacts schoolwork and life.

For some children, low Processing Speed may only require extra time to complete work. For other children, you may find that they will consistently struggle with writing and worksheet assignments, for example, but excel when given the opportunity to complete an alternative assessment or use adaptive speech-to-text technology. Finally, there are children who have deeper processing issues that require more dedicated efforts to support their learning needs.

Want to read more about low Processing Speed? Check out our blog post Fast, but Slow? Processing Speed and the Gifted Child written by neuropsychologist Dr. Chi Huang. Still not sure what your child’s evaluation results mean? Schedule a private consultation for a 2nd opinion on your test results today.